The World Forgot Us: Sinjar and the Yazidi Genocide

‘Thomas Schmidinger's book has great sympathy for the plight of the Yazidi people, does not come at the expense of leaving out some of the more controversial aspects of Yazidiism.’

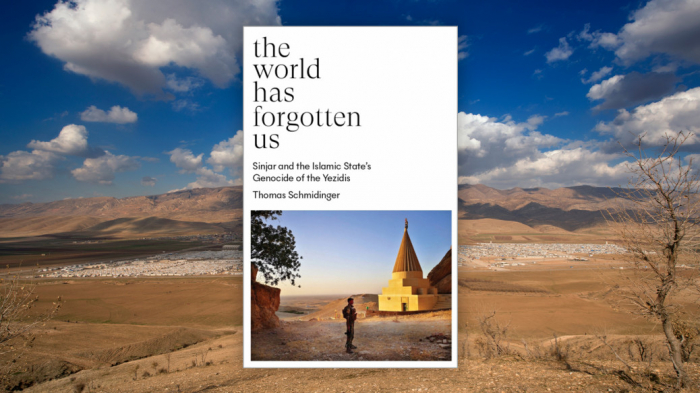

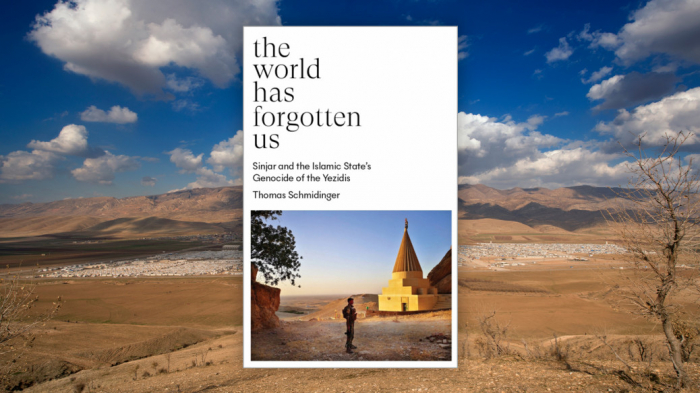

In his book The World Forgot Us: Sinjar and the Genocide of the Yazidis by the Islamic State, Thomas Schmidinger, a political scientist and anthropologist at the University of Vienna, presents two key realities.

On the one hand, ISIL's efforts to exterminate Yazidis are by no means an isolated event, but the culmination of centuries of discrimination.

On the other hand, the Yazidis are much more than just a long-persecuted people. Rather, they are a group with distinctive cultural and religious practices that have traditionally been poorly understood. One of the most common myths is that Yazidis worship the devil. Such an image has played a central role in the vilification of Yazidis over the centuries, and more recently in the dehumanisation that has led to massacres of Yazidis by members of ISIS.

‘The World Has Forgotten Us’ consists of two parts. The first is an essay covering the history of the Yazidis up to the present day. While it is logical that the focus of the historical account is on the past century, the reader would probably like to know more about the ancient history of the Yazidis, to which Schmidinger devotes several pages.

The second part of the book is a collection of interviews with prominent Yazidis conducted by the author over the years. The book also includes photographs taken by the Austrian academic during his field research.

One constant in the history of the Yazidis is the state's attempts to restore their autonomous organisation.

In the nineteenth century, various Ottoman generals were commissioned to impose taxation in Sinjar. In 1915, the Yazidi ancestral lands became a refuge for thousands of Armenian Christians fleeing Ottoman persecution. With the establishment of an independent state in Iraq and its consolidation in the following decades, the Yazidis were subjected to a new level of state intervention. For the Yazidis living in the Sinjar Mountains, ‘the period of Baathist rule of Iraq represented a massive caesura in their traditional way of life.’ (p. 46)

Under Saddam Hussein, indigenous Yazidis were deported from their villages and resettled in collective towns. The situation after the fall of the Iraqi dictator was not necessarily better. With the regime change, some Muslim Arabs resettled by Saddam in Sinjar began to gravitate toward the jihadist underground. They ‘viewed the United States occupation of the country and the presence of Kurdish militias as humiliating.’ (p. 53) In August 2007, two truck bombings orchestrated by al Qaeda killed more than 500 Yazidis.

The 2007 terrorist attacks were the prelude to the 2014 Yazidi genocide, recognised as such by the UN, the European Union and numerous national parliaments.

The ultimate responsibility for the atrocities committed against the Yazidis undoubtedly lies in the hands of ISIS members.

Despite this, many Yazidis believe that the peshmerga, the armed forces of autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan, could buy time for more Yazidi civilians to flee to the Sinjar Mountains and Syria.

In an interview with the author, Haidar Shesho, commander of the Yazidi militia HPÊ expressed his belief that ‘the PDK (the largest party in Iraqi Kurdistan) was quite content to leave Sinjar and that there was an agreement between them and ISIL to allow them to leave Sinjar before the attack on the Yazidis.’ (p. 178)

Weighing the various pieces of evidence, Schmidinger notes that the secret agreements made in those convulsive days were very opaque.

The Yazidis who suffered the worst fate lived in the southern Yazidi settlements of Iraq, further away from the Sinjar Mountains and northern Syria.

This was the case in Kocho, one of the collective cities established under Saddam. In that city, ISIS fighters killed some 600 men and boys. Women survived only to be enslaved and sexually abused. One of them was Nadiya Murad, a Yazidi human rights activist who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018.

It is clear that the Yazidis need help both inside Iraq and internationally to return to their ancestral lands with security guarantees, especially as former ISIS members continue to live in northern Iraq.

Thomas Schmidinger

Tags: #yazidisinfo #newsyazidis #aboutyazidis #genocideyazidis #iraqyazidis

The World Forgot Us: Sinjar and the Yazidi Genocide

‘Thomas Schmidinger's book has great sympathy for the plight of the Yazidi people, does not come at the expense of leaving out some of the more controversial aspects of Yazidiism.’

In his book The World Forgot Us: Sinjar and the Genocide of the Yazidis by the Islamic State, Thomas Schmidinger, a political scientist and anthropologist at the University of Vienna, presents two key realities.

On the one hand, ISIL's efforts to exterminate Yazidis are by no means an isolated event, but the culmination of centuries of discrimination.

On the other hand, the Yazidis are much more than just a long-persecuted people. Rather, they are a group with distinctive cultural and religious practices that have traditionally been poorly understood. One of the most common myths is that Yazidis worship the devil. Such an image has played a central role in the vilification of Yazidis over the centuries, and more recently in the dehumanisation that has led to massacres of Yazidis by members of ISIS.

‘The World Has Forgotten Us’ consists of two parts. The first is an essay covering the history of the Yazidis up to the present day. While it is logical that the focus of the historical account is on the past century, the reader would probably like to know more about the ancient history of the Yazidis, to which Schmidinger devotes several pages.

The second part of the book is a collection of interviews with prominent Yazidis conducted by the author over the years. The book also includes photographs taken by the Austrian academic during his field research.

One constant in the history of the Yazidis is the state's attempts to restore their autonomous organisation.

In the nineteenth century, various Ottoman generals were commissioned to impose taxation in Sinjar. In 1915, the Yazidi ancestral lands became a refuge for thousands of Armenian Christians fleeing Ottoman persecution. With the establishment of an independent state in Iraq and its consolidation in the following decades, the Yazidis were subjected to a new level of state intervention. For the Yazidis living in the Sinjar Mountains, ‘the period of Baathist rule of Iraq represented a massive caesura in their traditional way of life.’ (p. 46)

Under Saddam Hussein, indigenous Yazidis were deported from their villages and resettled in collective towns. The situation after the fall of the Iraqi dictator was not necessarily better. With the regime change, some Muslim Arabs resettled by Saddam in Sinjar began to gravitate toward the jihadist underground. They ‘viewed the United States occupation of the country and the presence of Kurdish militias as humiliating.’ (p. 53) In August 2007, two truck bombings orchestrated by al Qaeda killed more than 500 Yazidis.

The 2007 terrorist attacks were the prelude to the 2014 Yazidi genocide, recognised as such by the UN, the European Union and numerous national parliaments.

The ultimate responsibility for the atrocities committed against the Yazidis undoubtedly lies in the hands of ISIS members.

Despite this, many Yazidis believe that the peshmerga, the armed forces of autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan, could buy time for more Yazidi civilians to flee to the Sinjar Mountains and Syria.

In an interview with the author, Haidar Shesho, commander of the Yazidi militia HPÊ expressed his belief that ‘the PDK (the largest party in Iraqi Kurdistan) was quite content to leave Sinjar and that there was an agreement between them and ISIL to allow them to leave Sinjar before the attack on the Yazidis.’ (p. 178)

Weighing the various pieces of evidence, Schmidinger notes that the secret agreements made in those convulsive days were very opaque.

The Yazidis who suffered the worst fate lived in the southern Yazidi settlements of Iraq, further away from the Sinjar Mountains and northern Syria.

This was the case in Kocho, one of the collective cities established under Saddam. In that city, ISIS fighters killed some 600 men and boys. Women survived only to be enslaved and sexually abused. One of them was Nadiya Murad, a Yazidi human rights activist who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018.

It is clear that the Yazidis need help both inside Iraq and internationally to return to their ancestral lands with security guarantees, especially as former ISIS members continue to live in northern Iraq.

Thomas Schmidinger

Tags: #yazidisinfo #newsyazidis #aboutyazidis #genocideyazidis #iraqyazidis