Kidnapped and sold as a slave, this IS survivor wants to tell the story of Yazidi women

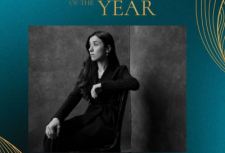

Badeeah Hassan Ahmed is among the few Yazidi women to speak publicly and share her story

Badeeah Hassan Ahmed used to believe that the Americans would come to her rescue if the IS attacked Kocho, a traditional walled village of Yazidis in north-western Iraq. When the IS came, one fateful day in August 2014, Badeeah found herself packed off, with six other women and four children, in a vehicle to Aleppo in Syria. There she heard a man introduce himself as a translator of al-Amriki, the American. But he wasn’t there to save her. The American-born IS general had just bought her as a slave.

It was a harrowing time. She was just 18 and the IS had forced her into human trafficking. As weeks turned into months, she held on to her then two-year-old nephew, Eivan, pretending he was her son, to lower her value in the slave trade.

After several attempts at fleeing from al-Amriki’s home, Eivan was taken away to be sold off. With nothing to lose, she looked al-Amriki in the eye and told him his acts were against Islam. “Under my gaze, he seemed to cower,” she writes. For the first time, she had control over him, and Eivan was returned to her.

A new life

Badeeah today lives in a modestly-sized house in quaint Tübingen with her husband, youngest brother and eldest sister. The minimally furnished living room with an open kitchen is awash with sunlight as Badeeah, dressed all in black, sits down on the carpet for the interview. Ahmed, 23, her husband, sitting on a corner chair, looks at her with visible pride throughout the hour-long conversation. “He left Iraq and came here for me,” she says, as they both giggle.

It took Ahmed, her childhood sweetheart, six months to escape Iraq. The two got married in Germany, and now their first child is on the way. “It’s a girl and we are naming her Mileva after Albert Einstein’s wife,” she says with a grin. When the child is born, Badeeah will tell her stories about Kocho before the IS attack, and about her life in Tübingen after seeking asylum.

What kept Badeeah going during her enslavement were childhood memories and a fervent faith in her religion. The Yazidis are an ethnic and religious minority in West Asia, with their largest population concentrated in Northern Iraq. They practise a monotheistic religion that has teachings and beliefs from various religions including Gnostic Christianity, Judaism, Sufi Islam and Zoroastrianism. Because of their distinct beliefs, Yazidis have often been labelled as “devil worshippers” and from 2014 onwards, the IS has waged a concerted attack against them, unleashing sexual violence on the women through slavery.

A safer world

IS fighters have raped Yazidi women and forcibly converted them to Islam by marrying them. Often, the children born of these alliances, along with their mothers, have been forced into exile because they are not accepted into their insular community. In her book, Badeeah describes her fear of returning home, how ‘al-Amriki’ frightened her that she would be rejected by her community. But Badeeah was welcomed by her family, and today practises her religion without restraint. “In fact, Easter is a big festival for us here,” she says smiling.

Badeeah is among the few Yazidi women to speak publicly and share her story. Through her book, she wants to empower not just Yazidi women, but all women affected by war and conflict. “I wanted to show that we can survive and fight,” says Badeeah. Her life in Germany bears no resemblance to the one she lived in Iraq. In Tübingen, she is provided state housing, has learnt German, and plans to study nursing. “I wasn’t allowed to study medicine in Iraq so I asked if I can do that here,” she smiles.

Badeeah had to undergo intensive therapy during her first three months in Germany. The therapist was accompanied by an interpreter who spoke Kurdish, Badeeah’s native tongue. Even though Badeeah no longer needs therapy, she feels triggered when she hears Syrian refugees in Tübingen speak Arabic. But one thing she understands — what the IS promotes is not Islam. “I have learnt that Islam doesn’t prescribe war or killing people or taking children away from their mothers,” she says. “For me, Islam is what I saw growing up.”

Badeeah is aware that her child will be born in a much safer world in Tübingen. She has no plans to move back to Iraq, even if there is political stability in the region. Eivan today is seven, speaks German, and lives with his mother in another part of Baden-Wurttemberg. Throughout her captivity, Badeeah recalled her mother’s words: “Always move to the light. Don’t let the darkness in. Hold onto love, so that the darkness will eventually be banished.” That’s what she continues to do, long after her nightmare is over.

Tags:

Kidnapped and sold as a slave, this IS survivor wants to tell the story of Yazidi women

Badeeah Hassan Ahmed is among the few Yazidi women to speak publicly and share her story

Badeeah Hassan Ahmed used to believe that the Americans would come to her rescue if the IS attacked Kocho, a traditional walled village of Yazidis in north-western Iraq. When the IS came, one fateful day in August 2014, Badeeah found herself packed off, with six other women and four children, in a vehicle to Aleppo in Syria. There she heard a man introduce himself as a translator of al-Amriki, the American. But he wasn’t there to save her. The American-born IS general had just bought her as a slave.

It was a harrowing time. She was just 18 and the IS had forced her into human trafficking. As weeks turned into months, she held on to her then two-year-old nephew, Eivan, pretending he was her son, to lower her value in the slave trade.

After several attempts at fleeing from al-Amriki’s home, Eivan was taken away to be sold off. With nothing to lose, she looked al-Amriki in the eye and told him his acts were against Islam. “Under my gaze, he seemed to cower,” she writes. For the first time, she had control over him, and Eivan was returned to her.

A new life

Badeeah today lives in a modestly-sized house in quaint Tübingen with her husband, youngest brother and eldest sister. The minimally furnished living room with an open kitchen is awash with sunlight as Badeeah, dressed all in black, sits down on the carpet for the interview. Ahmed, 23, her husband, sitting on a corner chair, looks at her with visible pride throughout the hour-long conversation. “He left Iraq and came here for me,” she says, as they both giggle.

It took Ahmed, her childhood sweetheart, six months to escape Iraq. The two got married in Germany, and now their first child is on the way. “It’s a girl and we are naming her Mileva after Albert Einstein’s wife,” she says with a grin. When the child is born, Badeeah will tell her stories about Kocho before the IS attack, and about her life in Tübingen after seeking asylum.

What kept Badeeah going during her enslavement were childhood memories and a fervent faith in her religion. The Yazidis are an ethnic and religious minority in West Asia, with their largest population concentrated in Northern Iraq. They practise a monotheistic religion that has teachings and beliefs from various religions including Gnostic Christianity, Judaism, Sufi Islam and Zoroastrianism. Because of their distinct beliefs, Yazidis have often been labelled as “devil worshippers” and from 2014 onwards, the IS has waged a concerted attack against them, unleashing sexual violence on the women through slavery.

A safer world

IS fighters have raped Yazidi women and forcibly converted them to Islam by marrying them. Often, the children born of these alliances, along with their mothers, have been forced into exile because they are not accepted into their insular community. In her book, Badeeah describes her fear of returning home, how ‘al-Amriki’ frightened her that she would be rejected by her community. But Badeeah was welcomed by her family, and today practises her religion without restraint. “In fact, Easter is a big festival for us here,” she says smiling.

Badeeah is among the few Yazidi women to speak publicly and share her story. Through her book, she wants to empower not just Yazidi women, but all women affected by war and conflict. “I wanted to show that we can survive and fight,” says Badeeah. Her life in Germany bears no resemblance to the one she lived in Iraq. In Tübingen, she is provided state housing, has learnt German, and plans to study nursing. “I wasn’t allowed to study medicine in Iraq so I asked if I can do that here,” she smiles.

Badeeah had to undergo intensive therapy during her first three months in Germany. The therapist was accompanied by an interpreter who spoke Kurdish, Badeeah’s native tongue. Even though Badeeah no longer needs therapy, she feels triggered when she hears Syrian refugees in Tübingen speak Arabic. But one thing she understands — what the IS promotes is not Islam. “I have learnt that Islam doesn’t prescribe war or killing people or taking children away from their mothers,” she says. “For me, Islam is what I saw growing up.”

Badeeah is aware that her child will be born in a much safer world in Tübingen. She has no plans to move back to Iraq, even if there is political stability in the region. Eivan today is seven, speaks German, and lives with his mother in another part of Baden-Wurttemberg. Throughout her captivity, Badeeah recalled her mother’s words: “Always move to the light. Don’t let the darkness in. Hold onto love, so that the darkness will eventually be banished.” That’s what she continues to do, long after her nightmare is over.

Tags: